In 1952, 10 years after her tragic death at Auschwitz, the New York Times called Edith Stein “one of the leading philosophical minds of our times” and a “heroically saintly figure in her adopted Church”.

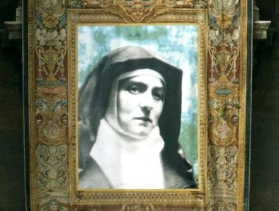

It underscores the chief paradox of Stein’s life: how a modern woman who became a Carmelite nun and saint – detaching herself from civilian life, immersed in contemplation – captivated the secular world. She still does on the 75th anniversary of her death at Auschwitz, on August 9, 1942.

Stein was born in Breslau, on October 12, 1891, the very day her large Jewish family was celebrating Yom Kippur, the holiest day in Judaism. Ever since her childhood – recounted movingly in her Life in a Jewish Family – Edith wanted to educate herself, and at a pace much quicker than was expected. Underlying that desire was a passionate search for truth – about the world, and the meaning of life – which led to an exploration of psychology and philosophy.

Her long search included a challenging period of atheism, beginning when she was a teenager, along with bouts of depression. But when she attended the University of Göttingen, studying under the philosophers Edmund Husserl and Max Scheler, a whole new world opened up to her.

Husserl was the founder of phenomenology, which teaches that one can discover objective truth and know “things as they are”, and that philosophy should consider all phenomena (including religious belief) when pursuing truth. Scheler, in turn, taught Stein about the coherence and beauty of Catholicism, which she grew increasingly impressed by. Finally, during the summer of 1921, visiting the estate of Hedwig Conrad-Martius, another pupil of Husserl’s, Stein found a copy of St Teresa of Avila’s autobiography, staying up all night to read it. After doing so, she exclaimed to herself: “This is the truth!” She was received into the Catholic Church the following New Year.

Stein’s conversion did not end, but rather deepened, her philosophical studies. These remain very relevant today. For instance, she emphasised that a believer must obey “the highest Lord”, which is never the state, but the human conscience, formed in the light of biblical revelation, and must be willing to assert itself – even in the face of conflict and persecution – for “religious values belong to a personal sphere, which the state cannot invade”. Even before she became a Catholic, Stein wrote An Investigation Concerning the State, warning against any efforts by immoral governments to segregate people into races or classes, or to suppress an individual’s conscience.

Stein was also an outspoken advocate for women, both before and after she became a Catholic, and wrote extensively on women’s issues throughout her adult life. She strongly opposed the petty and sometimes blatant discrimination women faced (and often still do). But there was one crucial element to Stein’s vision that differs markedly from so much feminist writing. She believed in the fundamental dignity and equality of the sexes, but never tried to blur their differences, or weaken the beauty of femininity. She defended the Church’s teaching on the family and human sexuality, but also foresaw an expanded role for women in the Church and society.

But at the heart of all Stein’s life and thought was her religion. Her faith in the Church’s teaching and the sacraments was unshakeable. (Some have claimed that Stein speculated about universal salvation, but as Richard Schenk OP has pointed out, this misrepresents her thought.) Her prayer life was exemplary, and she often spent hours on her knees in communion with God. She was deeply devoted to the Blessed Virgin, and wrote a brilliant treatise on St John of the Cross. The Passion constantly filled her thoughts, but she also drew strength from the Cross and the knowledge of the Lord’s ultimate victory over evil.

Suffering was another constant theme of Stein’s work. Her father died when she was two, there were other unexpected deaths among her relatives and friends, and she witnessed many soldiers’ pain while serving as a Red Cross nurse during World War I. But these trials only made her more attentive to others’ suffering, and led to her book On the Problem of Empathy, one of the philosophical classics of the 20th century. Empathy, as Stein shows, goes far beyond sympathy, in that it not only exhibits kindness and compassion for others, but seeks to understand and experience what they are going through.

Stein’s ultimate suffering came in 1942. As is well known, the Dutch bishops – after being warned not to do so – publicly condemned the Nazi deportation of the Jews. In retaliation, the Nazi Reichskommissar for the Occupied Dutch territories, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, ordered that Jewish converts to Catholicism be rounded up and deported. Among them were Stein and her sister Rosa, who were taken from a Carmelite monastery in Echt, along with many other converts, to die at Auschwitz.

After the war, Seyss-Inquart was arrested, tried and found guilty of committing war crimes. He was sentenced to death at Nuremberg, and executed in 1946. But before he was, he shocked the world by saying he deserved his punishment and making a strongly anti-Nazi statement. Before he was hanged, Seyss-Inquart returned to the Catholic faith of his youth, after receiving absolution from Fr Bruno Spitzl, the prison chaplain.

As the theologian John Hamlon said in a talk on this little-known episode: “The mystery of faith and redemption. I can’t imagine who was praying for him. Can you?”

![]()

This page is available to subscribers. Click here to sign in or get access.

Areas of Catholic Herald business are still recovering post-pandemic.

However, we are reaching out to the Catholic community and readership, that has been so loyal to the Catholic Herald. Please join us on our 135 year mission by supporting us.

We are raising £250,000 to safeguard the Herald as a world-leading voice in Catholic journalism and teaching.

We have been a bold and influential voice in the church since 1888, standing up for traditional Catholic culture and values. Please consider donating.